2007 – 2013

The first maps paintings were “Red River 1870s (beaded map),” (2006), and “Edmonton 1880s (beaded map),” (2006). I was researching Métis material history and was surprised to learn that Edmonton and Winnipeg were originally settled according to the Métis/Quebec style of river lots. I knew about my family’s river lot (lot 7) since childhood, but somehow didn’t make the connection that the whole settlement was divided by such lots. I painted the paintings because I wanted a record of this Métis trace.

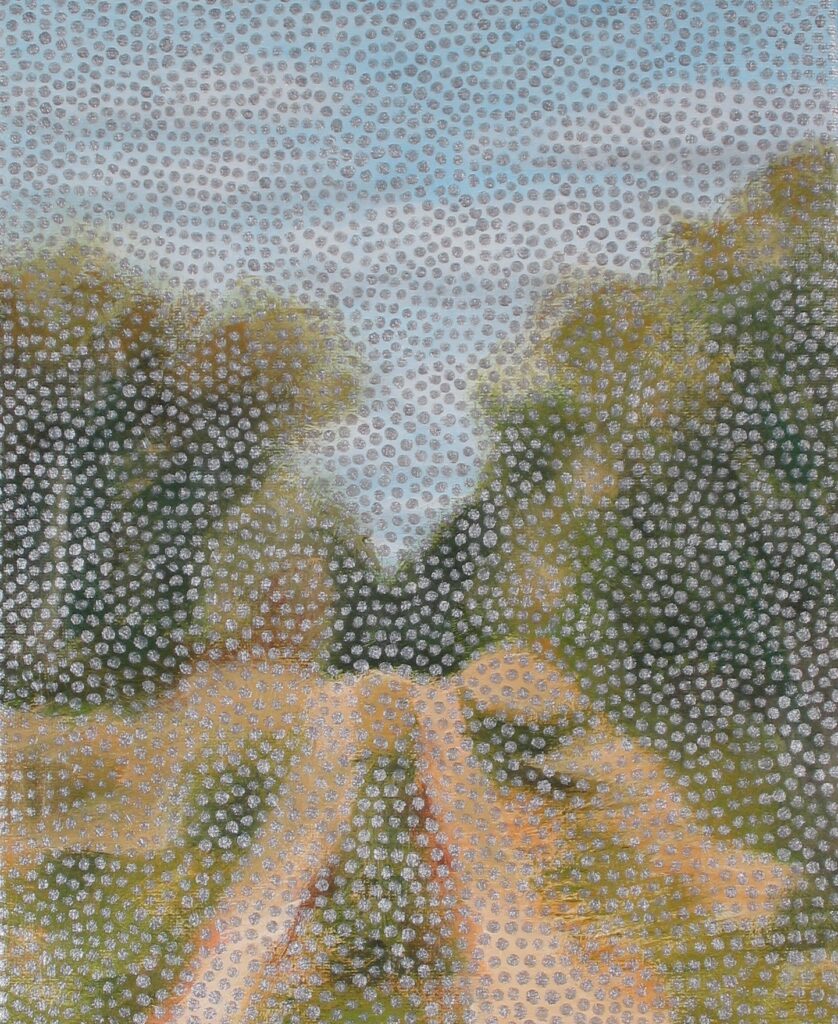

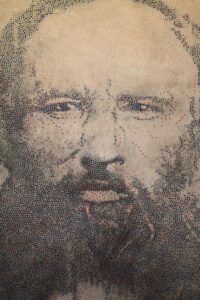

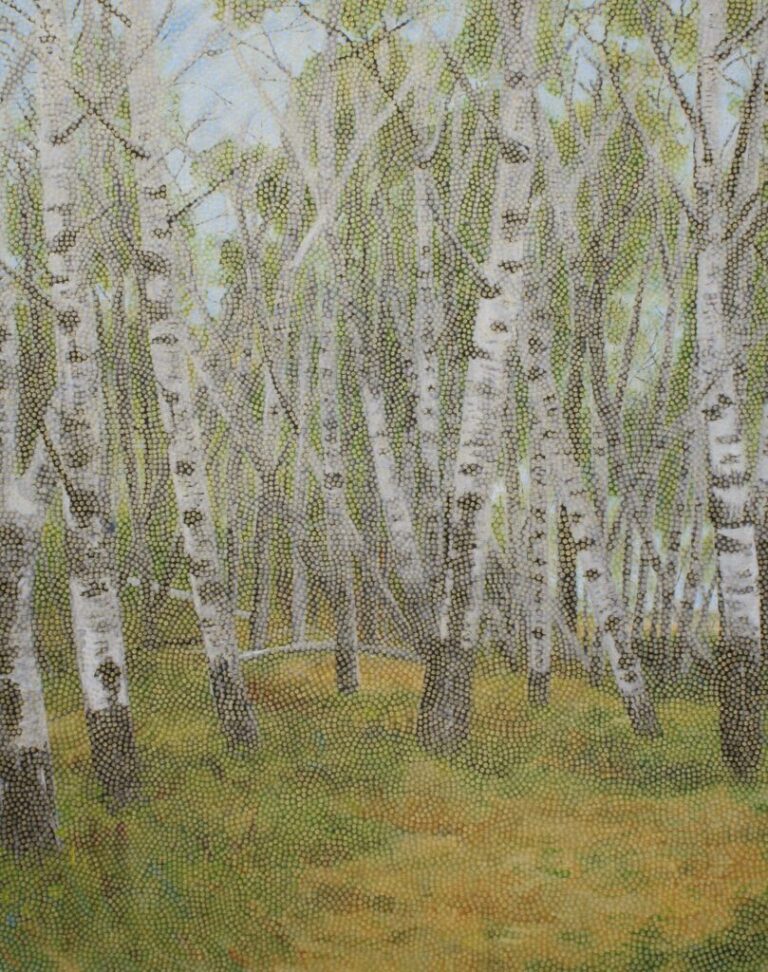

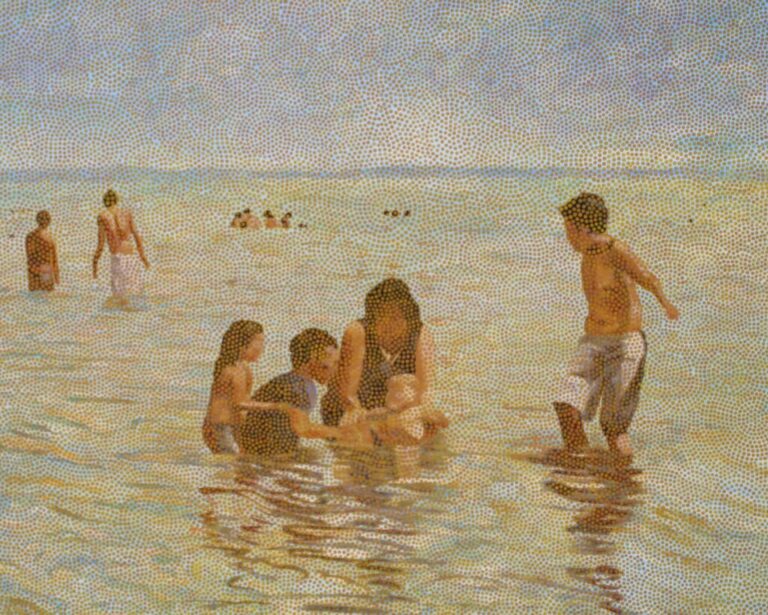

I had been making representational paintings of Métis history in styles informed by European art history traditions and American pop culture. I wanted to come up with a style informed by Métis material culture. I looked at beading. First, I tried beading. I wasn’t so good at it. I then decided to translate the beads into painted dots. The dots are rather random ways of filling space in these first efforts. In later paintings I play off specific traditional designs. I didn’t know about Christie Belcourt’s work or Aboriginal Australian dot painting until later. I was inspired by Alex Janvier’s maps. In 2008, I went to Australia where I learned that their dot paintings were also maps.

It was important to me to map the space that resides beneath and among the surface we think we know. I grew up knowing about river lot 7 but not how it was in a community, a Métis community of other river lot people. To find a way to make this record as art, as something that has a form that is identifiably Métis was also important. I wanted a form that had both continuity and was a translation that allowed me some artistic freedom to invent. Each of these paintings—including “Ste. Madeleine (beaded map),” acrylic on canvas, 122 x 153cm. 2006—is a land claim, a personal claiming of Métis territory and memory.

The map has people know that the way the city is currently laid out, in the case of Winnipeg, is influenced by the original design/inhabitants. While in Edmonton, the colonial design overwhelms the former design/inhabitants. Each painting is in a public collection. It is important to me that my work reaches a broad and thinking audience who will want to know more. My work is often used as teaching tools.

I was born and raised in Edmonton, Alberta. Because my father, Richard Garneau, was an amateur historian and genealogist I grew up knowing some of our Métis family history. He began this work in the 1950s and when he retired in the late 1990s, he published his research in a large website (http://metis-history.info/author.shtml). But it wasn’t until I was doing my own research that I discovered that Edmonton and Winnipeg were originally settled according to the Métis/Quebec style of river lots. I knew about my family’s river lot (7) since childhood but somehow didn’t make the connection that the whole Edmonton settlement was divided by such lots. Seeing the image, the map, made a more dramatic impression than words. Even though I walked the land there, I did not have this larger conceptual sense of the now erased history. My first maps paintings were “Red River 1870s (beaded map),” acrylic on canvas, 122 x 153cm. 2006, and “Edmonton 1880s (beaded map),” acrylic on canvas, 122 x 153cm. 2006. I painted these maps because I wanted a public record of Métis habitation in my hometown and elsewhere.

It was important to me to map the space that resides beneath and among the surface we think we know. I grew up knowing about river lot 7 but not how it was part of a community, a Métis community of other river lot people. To find a way to make this record as art, as something that has a form that is identifiably Métis was also important. I wanted a form that had both continuity and was a translation that allowed me some artistic freedom to invent. Each of these paintings is a land claim, a reclaiming of Métis territory and memory. The map has people know that the way the city is currently laid out, in the case of Winnipeg, is influenced by the original design/inhabitants. While in Edmonton, the colonial design overwhelms the former design/inhabitants. Each of these map paintings is in a public collection. I want my work to reach a broad audience who wants to know more about our shared histories. My work is often used as teaching tools.

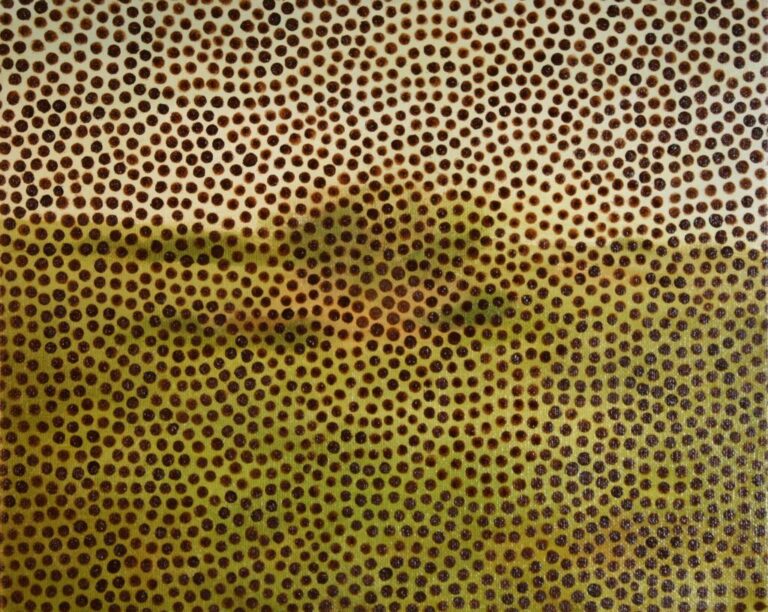

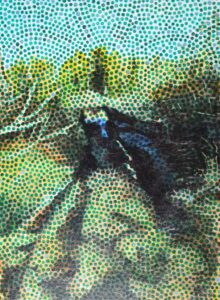

My first map painting attempted to recover erased histories of Métis presence. While I was painting a series of small river lot paintings (2012) that depicted the Batoche region I had an unpleasant revelation. I liked these maps because they were among the few places where river lots remain. They stood in contrast with the square lots and felt like resistance to the colonial grid. The grid was imposed on the Prairies following the founding of Canada in 1867. It over-wrote existing land claims, including those of the Métis. The system is a rational system imposed on organic sites. Over time—with the imposition of grid roads, for example, the conceptual map reshapes real space. The Métis/French river lot attaches community in relation to the river and each other. Even so, it is still a colonial system of settlement—French/Métis rather than British. In contemplating the Batoche maps as I painted them; I began thinking about Métis complicity in colonization. “Cultured Nature” and “Responsive Community” are among the paintings the respond to this implication. Both are fictional maps. “Responsive Community” suggests that while Métis river lots respond to the river more organically than do grid lots, they still attempt to settle and order nature. “Cultured Nature” is more direct. The farms control the land; the river persists. Southern Saskatchewan is a particularly depressing space as the land has been nearly completely gridded and converted from nature to culture—it is cultivated. Shorn of their names, measures, and usual functions, I intend these painted maps to cause the viewer to reconsider the spaces they occupy. I want folks to be aware of erased Métis presence; the competing types of settlement and their effects, and what we have lost by industrializing the landscape rather than co-habiting with it. At the same time, I want to recognize the complicity of Métis settlement in the colonial story and our co-authoring of the distortion of these spaces.

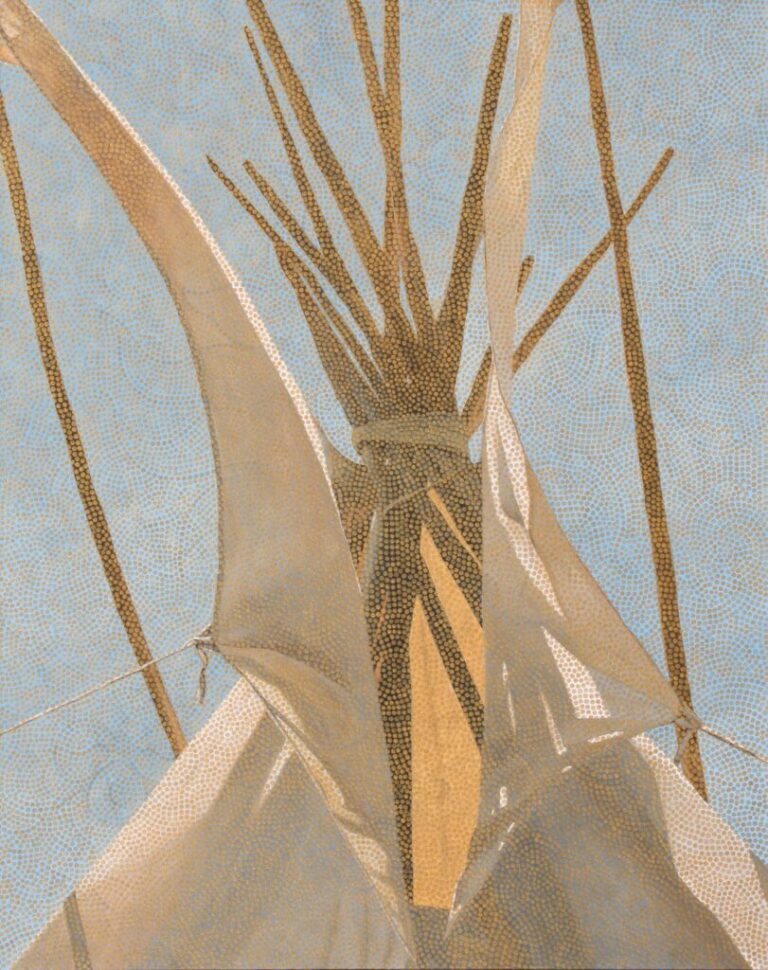

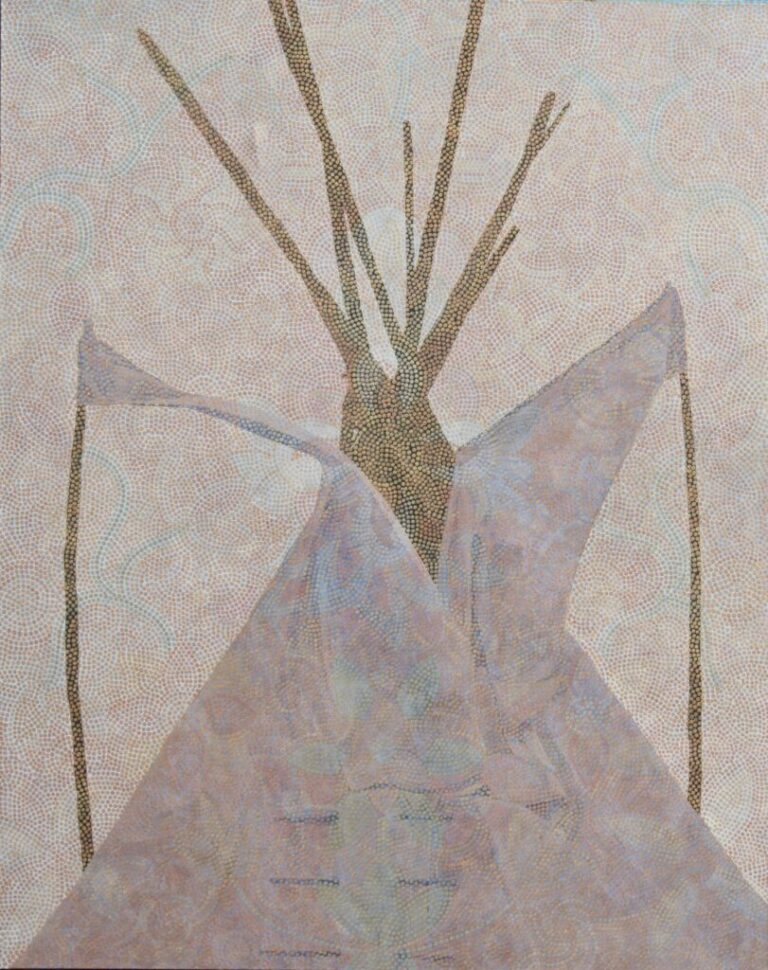

With the beaded tipi paintings:

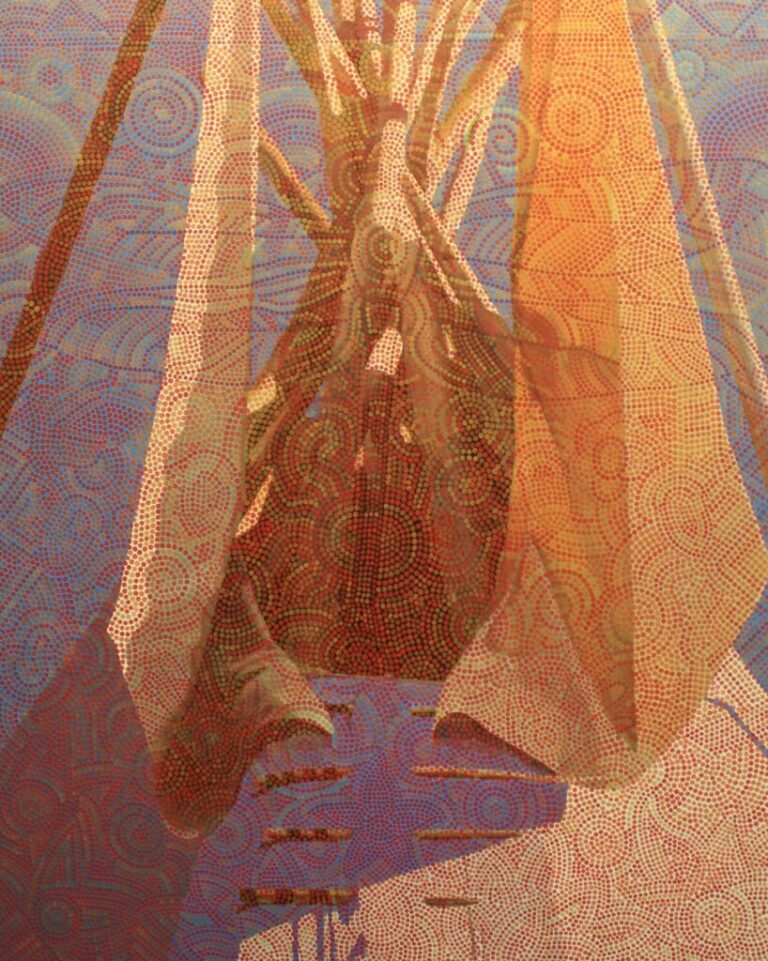

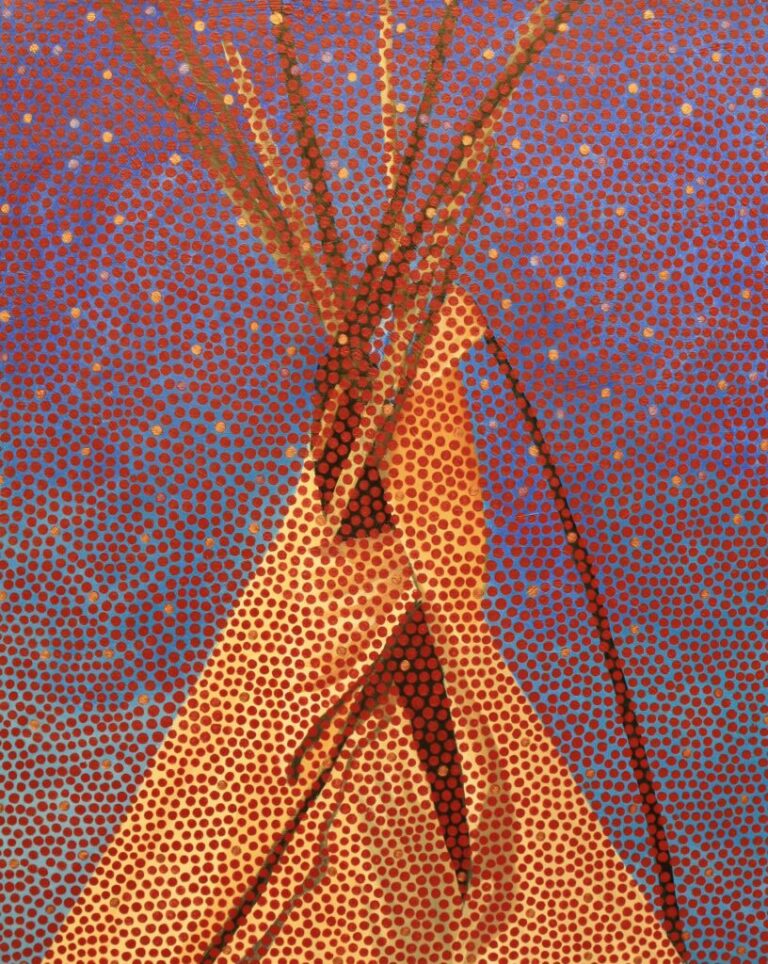

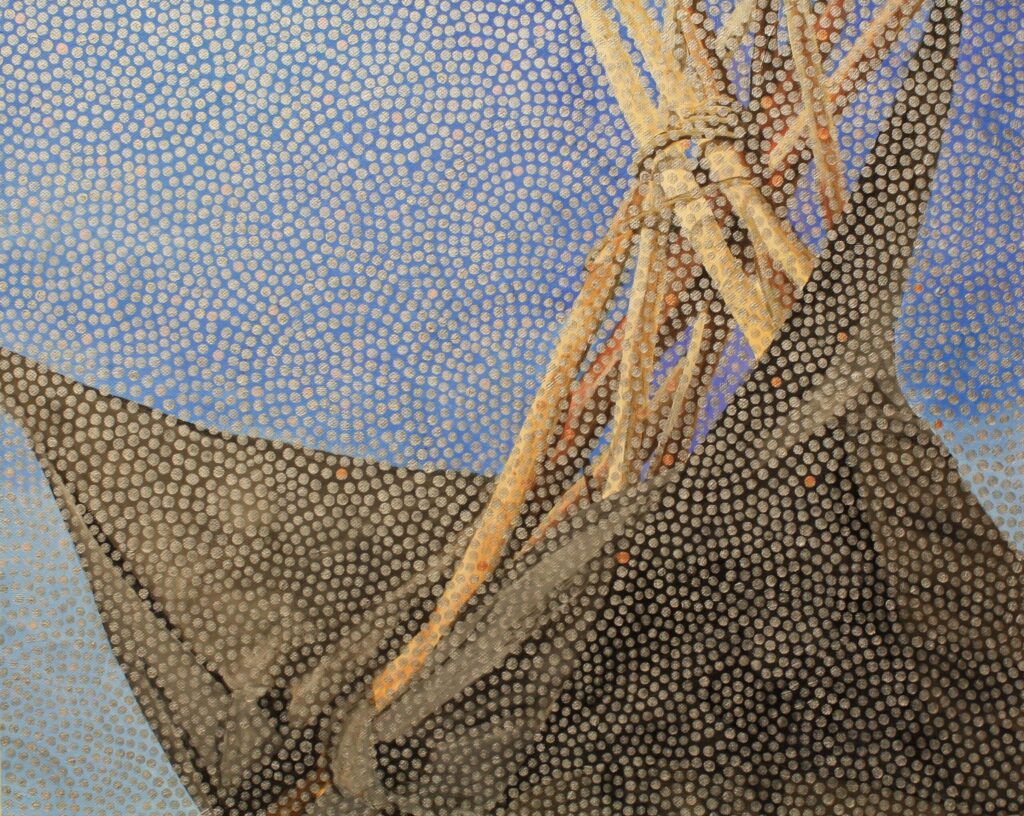

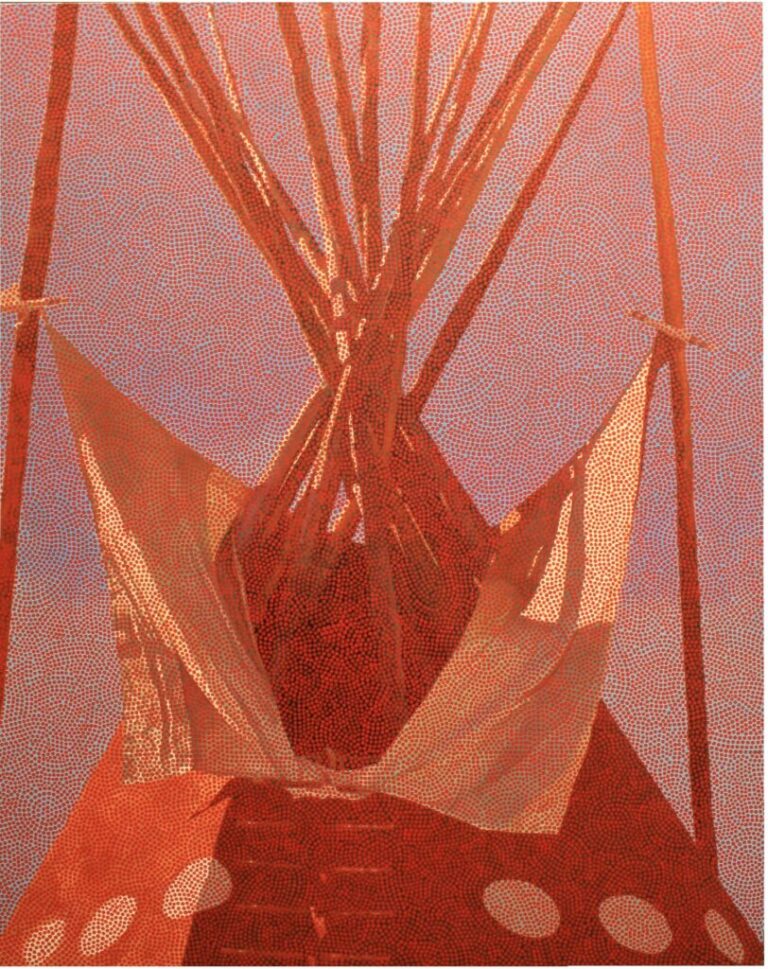

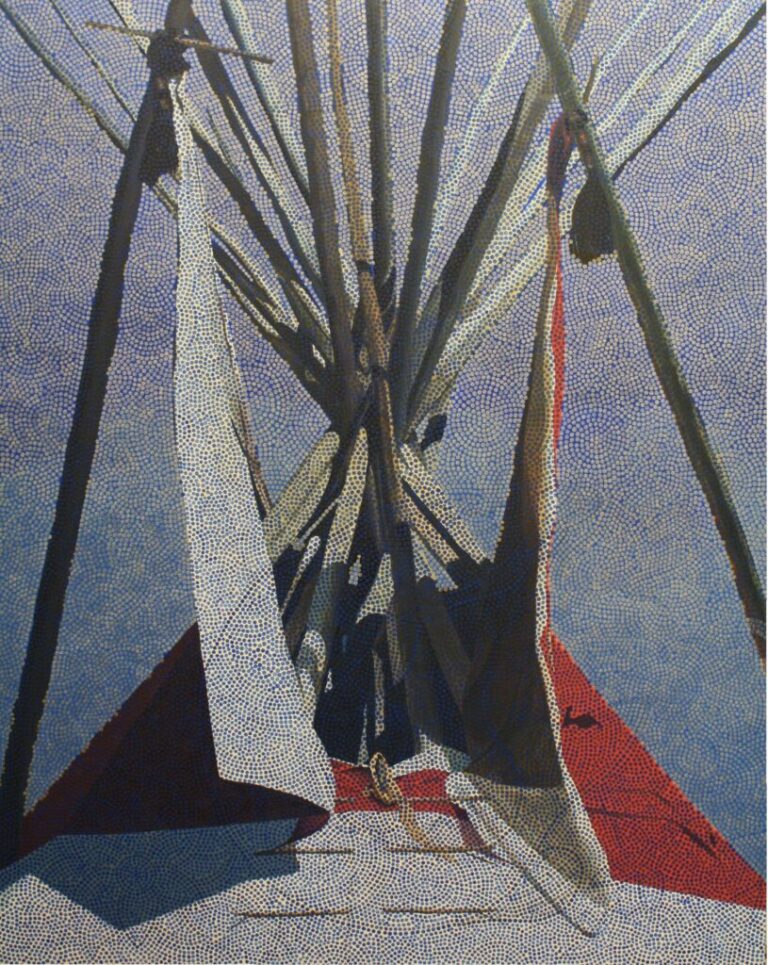

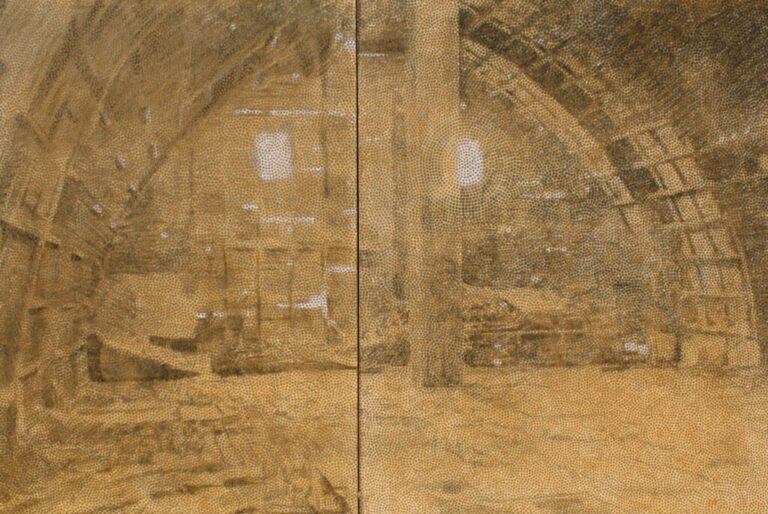

These paintings are rendered in a ‘beaded’ style. The screen of dots are inspired by the beadwork of the Métis, the “flower bead people,” but they also reference Western traditions such as Seurat’s pointillism, Ben Day dots in old comics, Lichtenstein, Pop and Op art, Chuck Close and Australian Aboriginal painting. The dots in all these sources, except the last, are formal arrangements without much meaning in themselves. The dots in my paintings are arranged to suggest Métis beading designs and therefore a Métis presence or point of view. Laid over a landscape, the beads suggest that this is, or once was, a Métis site. I want the viewer to see the scene through Métis eyes. At the same time, the dots act as a screen suggesting that the gaze is partial and incomplete. Some of the new paintings have more complex images in these screens of dots. These paintings not only have the flowers and abstract shapes found in Métis beading but also fish, a dragon fly, the shapes of hands and other things.

Tipis are a First Nations design that evolved due to the introduction of European fabric. This is a métissage—mixing of two cultures. I choose to paint the tops of these structures to emphasize the meeting of earth (material realm) and sky (metaphysical realm) with a human-made structure as the meeting point.

I painted “Shingwauk (Tears and Sun)” after visiting the Shingwauk Indian Residential School in 2012. I gave a keynote talk there and our group toured the site. The guide told us how the children spent little time in the classroom. More often they were labourers, growing food, etc. The guide also showed us the large graveyard, and a smaller, unmarked plot that might hold the bodies of children who died at the school. The painting is of tipi that was set up between the school and those burial sites during my visit. This painting is last in a series of sixteen ‘beaded’ tipi paintings I did at that time. The bead screen is made up of small swirls of paint meant to evoke Indigenous beading. This screen features drops that could be tears or rain. There is a ring (sun) of beads where the poles cross. The tipi represents the body. The wrap is like a skirt, the poles, ribs, the hearth a womb. The poles that shoot up past the crossing are undraped and suggest the metaphysical body extending to the stars. I was moved by the fact that the folks who went to the school as children didn’t call themselves survivors but alumni. They did not want to be defined and defeated by their time there. The sun and gold beads read as optimistic to me. The tears/rain brings new life.