This section brings together all selected writings on contemporary art, exhibition practices, and Indigenous representation. The texts are also organized thematically and can be accessed through the menu under the following sections: “Accessibility”, “Art Exhibitions”, “My Art and Curation”, “Conciliation”, “Cultural Appropriation”, “Indigenous Art, Display, and Criticism”, and “Other Writing”.

Replying to a colleague who was defending a friend, Winston Churchill famously quipped, ‘He is a humble man, but then he has much to be humble about!’ I resemble that remark. I am neither a museum curator nor anthropologist, not a PhD of any strain. I curate art, mostly Indigenous, in Treaty Four and Six territories. I am an artist who teaches painting and drawing at a regional university in Canada, Saskatchewan, Regina—the very trifecta of modesty. Ironically, in the inverted worlds of the contemporary museum and academy, where margins often centre, having much to be humble about can be a quality.

From Artifact Necropolis to Living Rooms: Indigenous and at Home in Non-colonial Museums (excerpts)

I wonder about artistic privilege. The advantages, attention, and public money granted to select artists, but especially the social margin, passage, and exception we occasionally enjoy. In exchange, artists make the absent present. We reflect the fleeting known in condensed, beautiful, novel, and more permanent or replicable forms. We recite, repeat, refresh, and invent. Artists fabulate the real. We devise the displays by which a people know and show themselves. We entertain. We educate without looking you in the eye.

An Uncertain Latitude

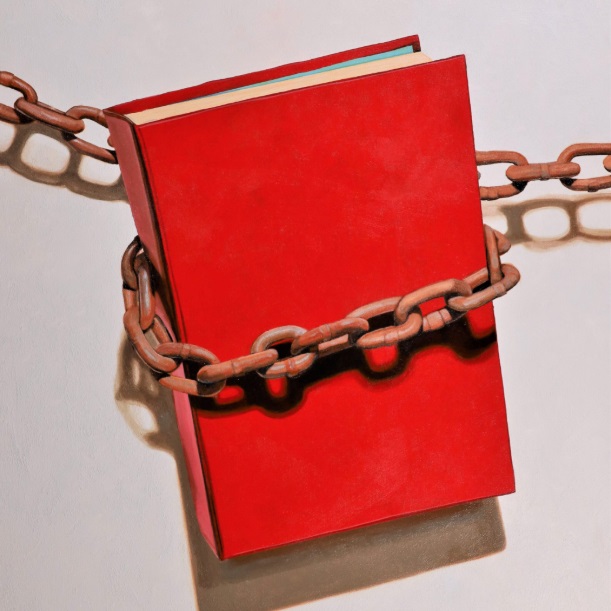

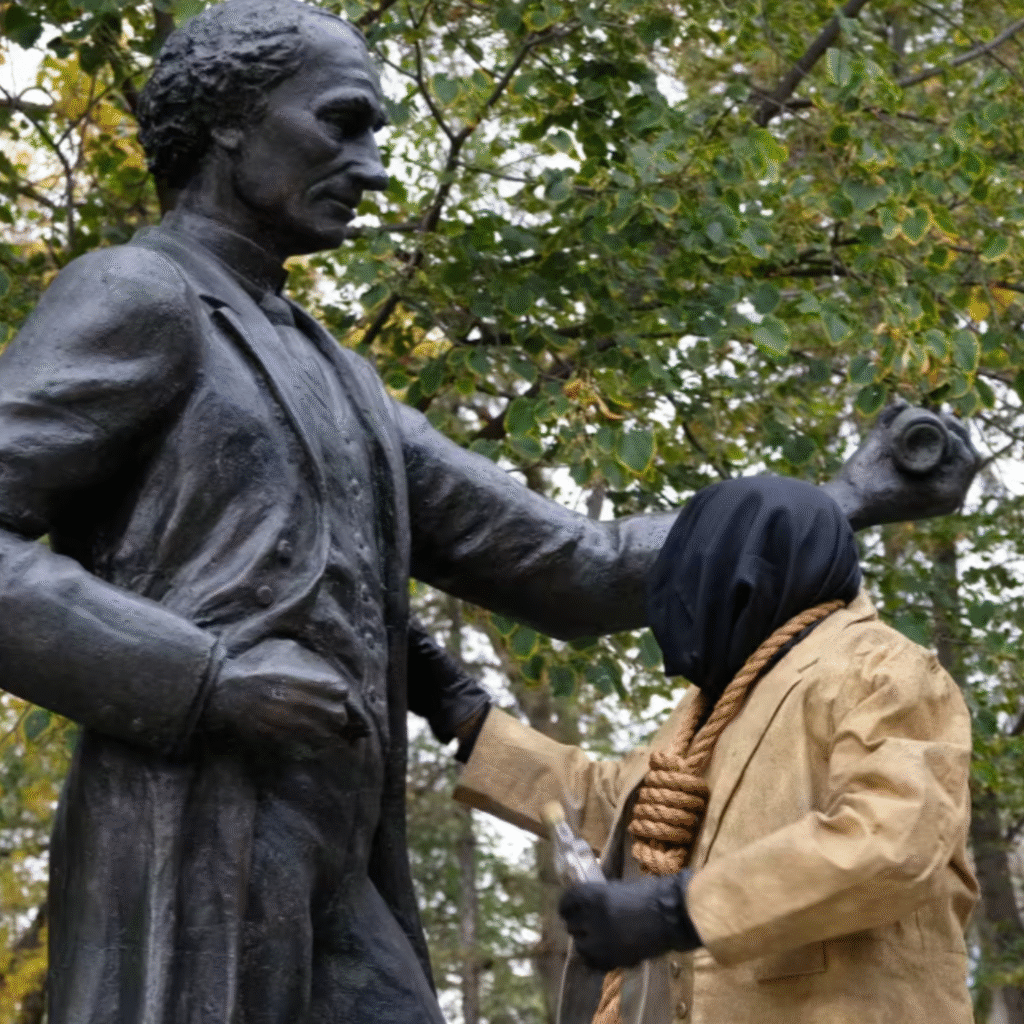

I am conflicted about the recent vandalism and destruction of colonial statues and churches in Northern Turtle Island. As a visual artist and writer who tries to make meaningful and well-made things, and who appreciates how difficult and fragile art and consciousness are, I distrust the direct, the rapid, and the destructive. Born with a preference for reason over passion, I am compelled to collect and evaluate the facts before judging, before acting. The problem with reason, however, is that it can be too reasonable. Slow, cool calculations oil the machinery of the status quo and discourage passionate action—any disruptive action, really—beyond opining or art making. And, at times like ours, both reason and art fail to satisfy the need for radical change.

Reason for Passion