This section brings together all selected writings on contemporary art, exhibition practices, and Indigenous representation. The texts are also organized thematically and can be accessed through the menu under the following sections: “Accessibility”, “Art Exhibitions”, “My Art and Curation”, “Conciliation”, “Cultural Appropriation”, “Indigenous Art, Display, and Criticism”, and “Other Writing”.

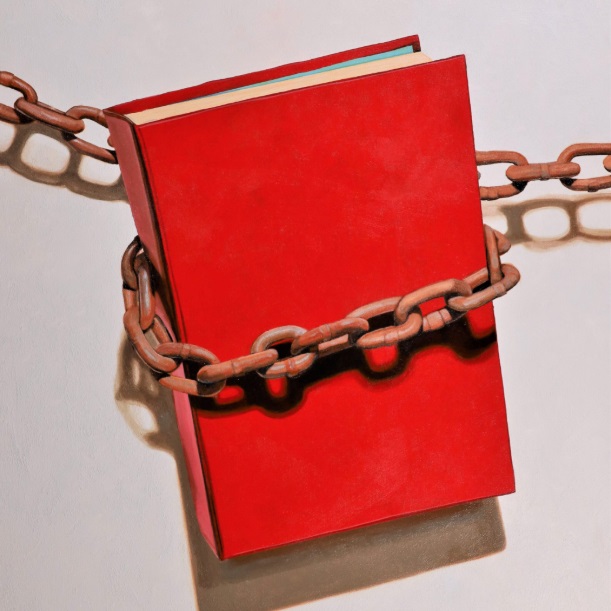

Most Canadians and Americans believe they live in post-colonial countries, independent since 1867 and 1776, respectively. However, First Nations, Inuit, Métis, and American Indians living in these same territories remain under imperial control. Their lands are occupied, not by Britain, but by Canada and the United States. There is a growing drive to decolonize art exhibitions, museums, universities, and most everything else. If these efforts are predicated on ideas and practices from states where imperialists have actually left, they must be re-tooled to be meaningful in places where settlers have no such plans.

Settler Decolonialism and Indigenous Non-colonialism in the Visual Arts

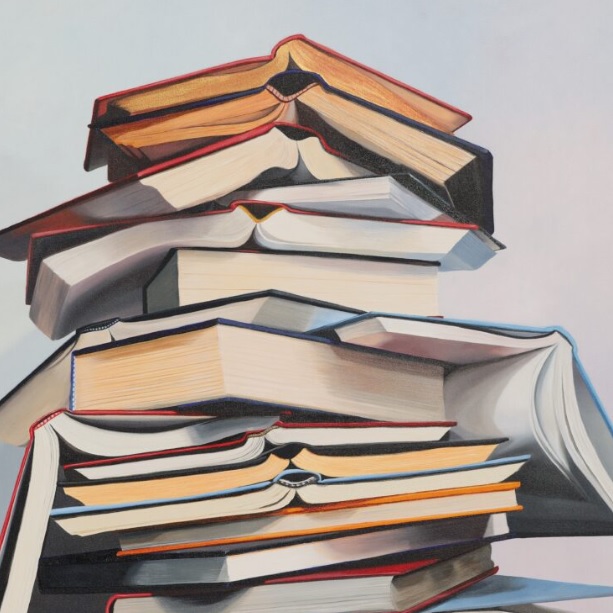

Duchamp once said that works of art have a shelf-life of about a decade. Masterpieces might retain their validity for 50 years. I think he was serious. I think he was right, exempting, of course, his own work. It is the fate of successful art movements that, as the world catches up to their innovations, the individual objects lose their original power: the capacity to shock, to confuse in a meaningful way, to incite, to embarrass, to make you see – and even want to live – differently. Such works become museum pieces, exemplary, canonical, nostalgic.

Messages Beyond the Medium

Aesthetic distance dissolved into carnality on a humid summer afternoon at the Art Institute of Chicago. I was seized at first sight by an urge to press my lips to those full, slightly parted ones. And, once the security guard ambled out of sight, I did. Of course, I wanted to kiss the beautiful person represented by the sculpture, but—for my teen-aged self, chaste by introversion but eager by design—this cool intermediary would do. But it didn’t. Knowing, and yet not fully feeling it until I tried it, the result of my Pygmalion performance was inevitable—erotic disappointment, a sense of bathetic absurdity, but also the excitement of breaking a rule.

Marginalized by Design

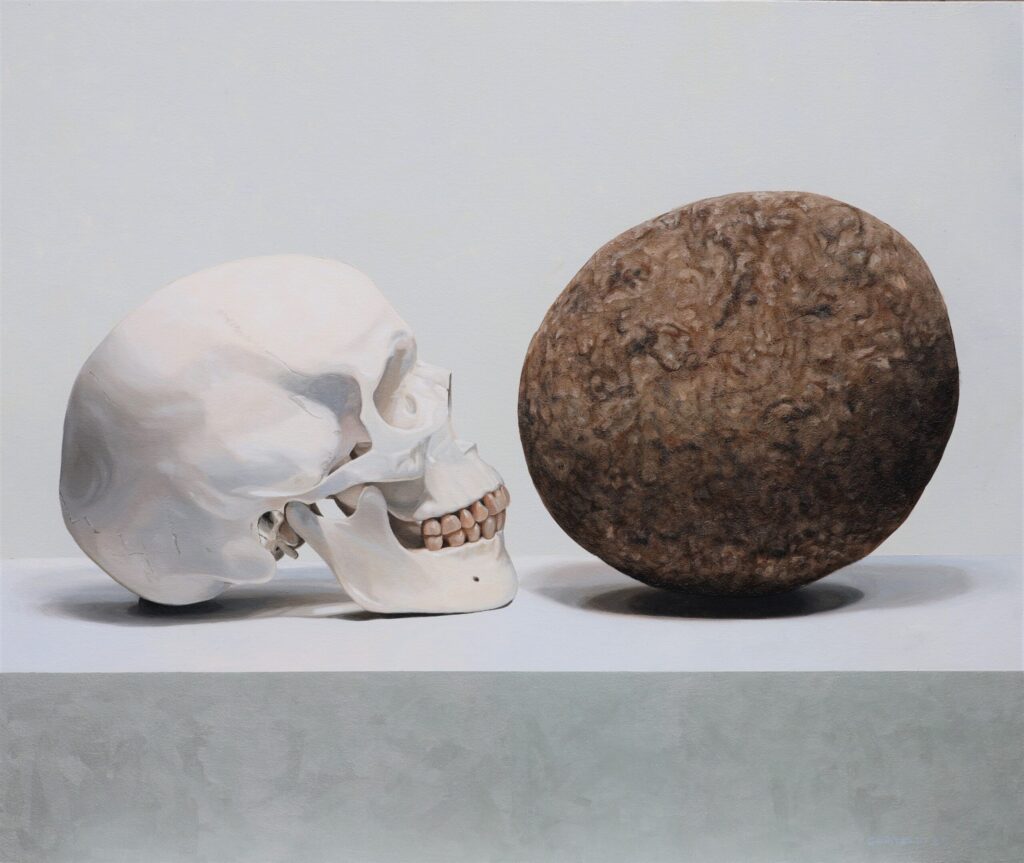

The final report of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission begins: “For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada.” The rest is footnotes—sober, thorough, harrowing, insightful, and moving descriptions of the mechanisms and effects of the slow, relentless genocide machine.

Indigenous Creative Sovereignty after Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation

Replying to a colleague who was defending a friend, Winston Churchill famously quipped, ‘He is a humble man, but then he has much to be humble about!’ I resemble that remark. I am neither a museum curator nor anthropologist, not a PhD of any strain. I curate art, mostly Indigenous, in Treaty Four and Six territories. I am an artist who teaches painting and drawing at a regional university in Canada, Saskatchewan, Regina—the very trifecta of modesty. Ironically, in the inverted worlds of the contemporary museum and academy, where margins often centre, having much to be humble about can be a quality.

From Artifact Necropolis to Living Rooms: Indigenous and at Home in Non-colonial Museums (excerpts)

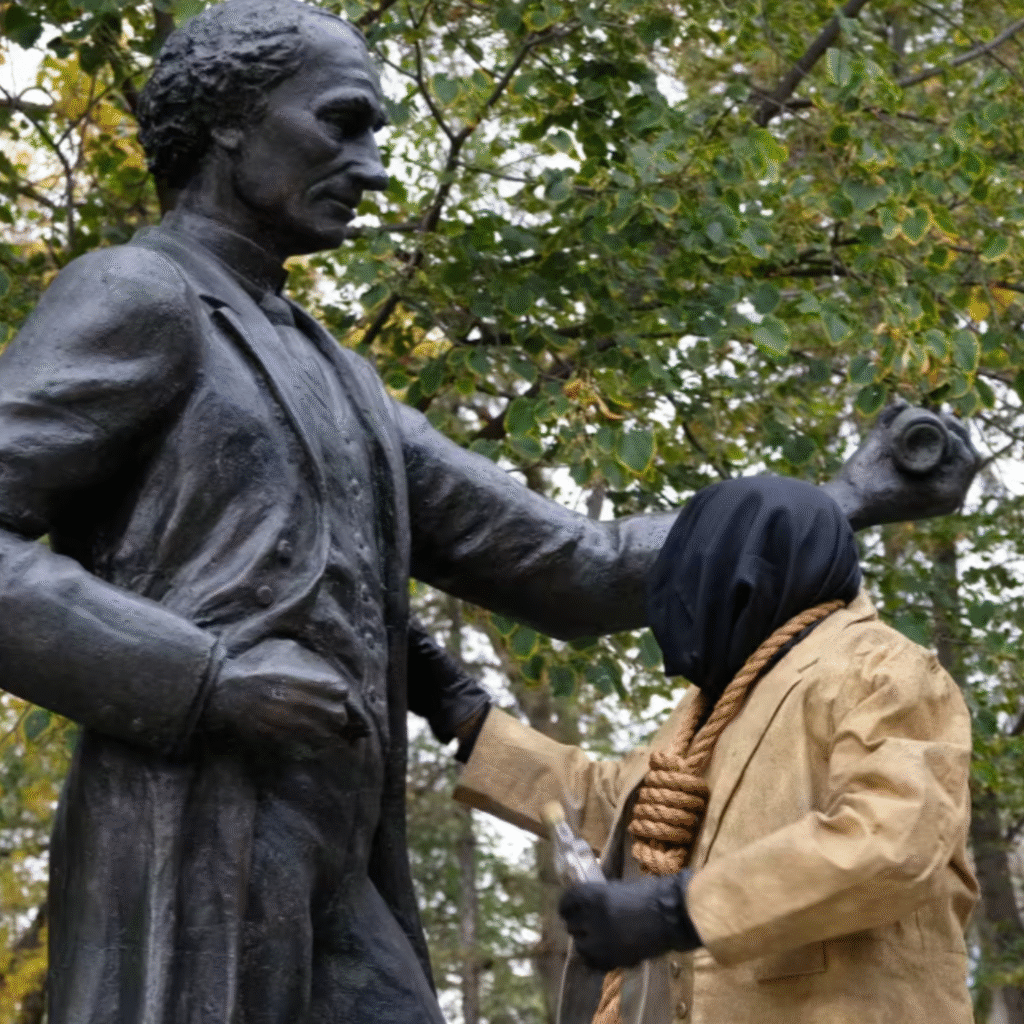

On a freezing winter afternoon in Regina’s Victoria Park, about fifty people gather at a sculpture of John A. Macdonald (1815-1891). Macdonald was Canada’s first Prime Minister. He also stewarded policies designed to subdue and aggressively assimilate the original inhabitants of Northern Turtle Island. These measures included: reserves; Pass laws restricting First Nations travel, trade, and political organizing; the Indian Act, which among other things, outlawed traditional cultural, spiritual, legal, and governance practices; and Indian Residential Schools, which separated children from their families, land, and languages, and were meant to extinguish Indigenous ways of being and knowing, and eventually title, from future generations.

Extra-Rational Indigenous Performance: Dear John; Louis David Riel

It’s been four years since I experienced the exhilarating yet numbing anarchy of Dhaka traffic. Picture streets dense with transport trucks, vans, cars, pedaled and motorized rickshaws threading a crazy quilt stretching to the blurred edges of one of the worlds’ largest, most populous, and polluted cities. Vehicles oscillate between aggression and diplomacy, their electric-quick negotiations produce a flowing tangle. Smell the sub-tropical humidity infused with sweat, cooking odors, and the acrid emissions of industry. Hear the horns, engines, and shouts.

Dhaka Traffic: Disabled by Design—an Allegory

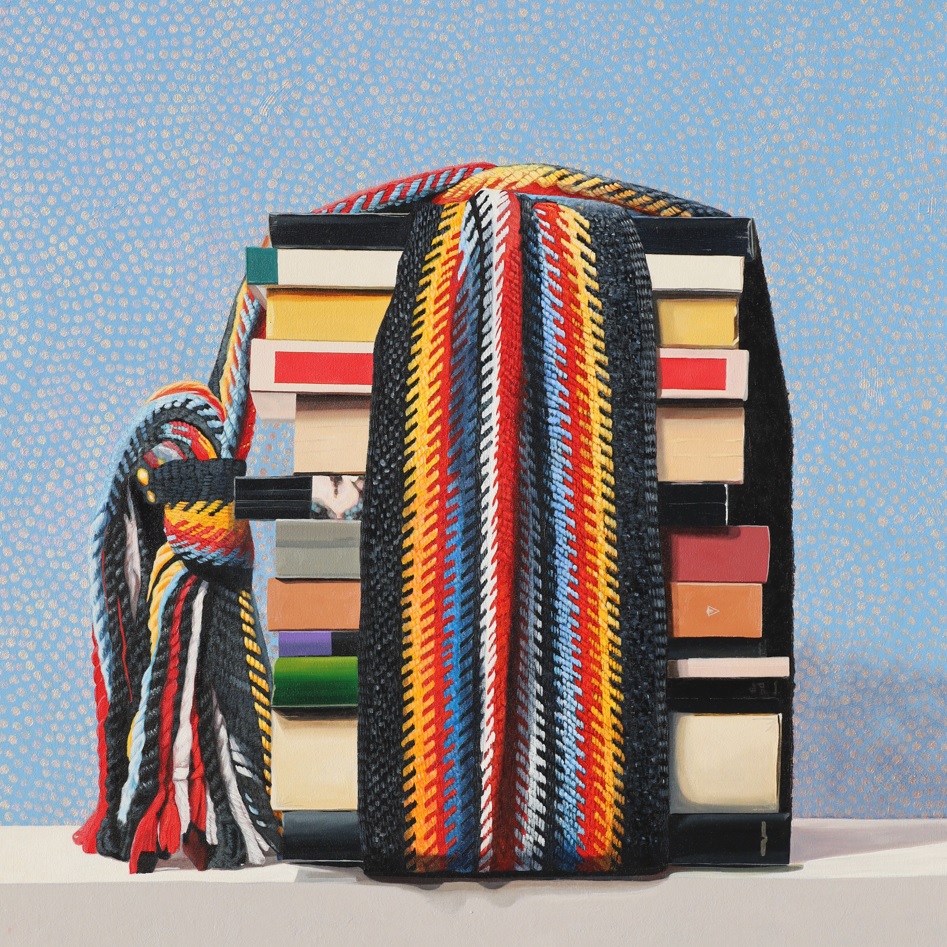

Snow and rain. Escaping the slushy, wet darkness, seven people gather in a circle around a generic grey blanket. In the centre are several oversized cedar dice incised with words. The first reads “I am,” “you are,” “we are,” and “they are.”

The second reads “fairly,” “deeply,” “very,” “so,” “not,” and “somewhat.” The final die has five sides reading “sorry,” and one with “tired of this” carved into it. The possibilities and combinations disassemble and reassemble as everyone reaches for the dice to smell and feel their heft, their smooth rounded sides.

APOLOGY DICE: COLLABORATION IN PROGRESS

I wonder about artistic privilege. The advantages, attention, and public money granted to select artists, but especially the social margin, passage, and exception we occasionally enjoy. In exchange, artists make the absent present. We reflect the fleeting known in condensed, beautiful, novel, and more permanent or replicable forms. We recite, repeat, refresh, and invent. Artists fabulate the real. We devise the displays by which a people know and show themselves. We entertain. We educate without looking you in the eye.

An Uncertain Latitude

I am conflicted about the recent vandalism and destruction of colonial statues and churches in Northern Turtle Island. As a visual artist and writer who tries to make meaningful and well-made things, and who appreciates how difficult and fragile art and consciousness are, I distrust the direct, the rapid, and the destructive. Born with a preference for reason over passion, I am compelled to collect and evaluate the facts before judging, before acting. The problem with reason, however, is that it can be too reasonable. Slow, cool calculations oil the machinery of the status quo and discourage passionate action—any disruptive action, really—beyond opining or art making. And, at times like ours, both reason and art fail to satisfy the need for radical change.

Reason for Passion